There had always been doubts about immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in particular the Ukrainians who had settled much of the West.

The British establishment often viewed them as a threat, as Oxford trained Elizabeth Mitchell wrote, “ Can Canada… afford to base herself on an ignorant, non-English speaking peasantry, winning a bare living by unceasing labour?”

Those who had been worried about Ukrainian peasants dragging down Canadian society and destroy the British character of the country now used the war as justification to do something about them.

Although the RCMP (then the Northwest Mounted Police) had investigated and found no reason for alarm, public pressure was growing because of the growing number of Ukrainians moving from the farms to the cities in search of work.

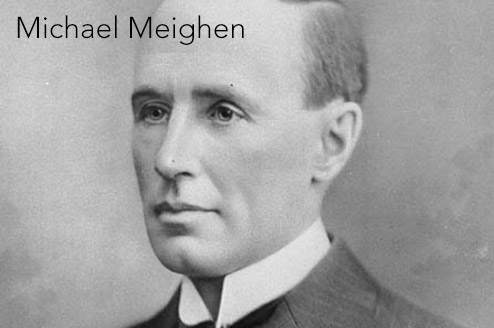

Future Prime Minister Meighen expressed the public sentiment this way, “they were out of work and in that state were a menace to the community.”

The Federal Government responded with an ‘enemy’ registration policy in the War Measures Act of 1914.

Ukrainians living in cities were required to register and report monthly. Those still on farms were excluded, because they were not seen as a threat.

Nevermind that all of these Ukrainians had left the Austro-Hungarian Empire behind, in search of a new life, new opportunity, and new freedom, they were still objects of suspicion.

Within weeks, several hundred unemployed men were rounded up by police and sent to work camps. Eventually over 8000 were detained by the Federal Government.

In selecting detainees, the government confined German nationals in jail-like settings, but German immigrants who had become Canadian citizens were generally left alone.

Ukrainians on the other hand, were treated differently.

Before the war, many worked at heavy labor under primitive conditions for resource and railway companies. So to the Canadian Government, it made perfect sense to have them do the same kind of work during their detention.

The majority were put to work in what is now Banff National Park, contructing a new road to Lake Louise.

Similar work was done near Mount Revelstoke, only this time up the side of a mountain. With the approach of winter, the men were transferred to Yoho, where they worked on a highway to Kicking Horse River.

The remains of that camp still exist today, it was simply left to decay.

By the end of the first season, parks officials found the work to be satisfactory, but complained about the slow progress. One must wonder what more could be expected from men with only hand tools and wheelbarrows.

The internees were also desperately unhappy.

Not only did the men bitterly resent their captivity – many could not understand why they were being treated as traitors – and they recoiled at the forced labor under harsh conditions.

Some quietly waited for the right moment to escape, even though guards were under orders to shoot.

Release, if it could be called that, came in 1916 when Canadian military commitments in Europe made a serious labor shortage at home. The government figured that the interned aliens might as well fill wartime vacancies as long as they reported regularly to the local police.

The men at Yoho in the meantime, had decided to speed up their release. Using shovels and table cutlery, they had started digging a tunnel. By the time it was discovered it was just 8 feet from freedom.

The camps were closed in the fall of 1916.

Park officials regarded the internment camps as a mixed blessing, they had great expactations and were dissapointed at what had actually been achieved. At the same time, Commisioner Harkin had to admit that the men had tackled jobs that would have otherwise been impossible during the war.

There was a sadly ironic aspect to the park internment program.

Throughout the war, Harkin was extolling the virtues of the National Park system, and how these special places would provide sanctuary when the guns fell silent.

But in making the wonders of Banff, Jasper, Yoho, and Mount Revelstoke more accessible, the internees had known only exhaustion, suffering, and desolation.

After the war, the Ukrainian internees went back to their lives without restitution, recognition, or even an apology. It’s not really in the Ukrainian character to complain, or protest, or even expect any help other than that they can give to themselves.

Meanwhile, Commisioner Harkin had a lovely mountain named after him.