This was the conclusion of a University of California study, which wrote that human life expectancy was the determining factor for endangered birds and mammals.

Though this idea is not a pleasant one, it is surprisingly popular.

People love animals after all. Some want to look at them, some want to communicate with them, and others just want to eat them. Regardless, we are all fascinated by them.

So what’s the problem?

According to the World Wildlife Fund:

Unlike the mass extinction events of geological history, the current extinction challenge is one for which a single species – ours – appears to be almost wholly responsible.

That is a pretty damning conclusion, and though widely accepted, it would probably be a good idea to define exactly what the “current extinction challenge” is.

Again, according to The World Wildlife Fund:

Firstly, we don’t know exactly what’s out there. It’s a big complex world and we discover new species to science all the time. So, if we don’t know how much there is to begin with, we don’t know exactly how much we’re losing.

So on what basis do they raise the alarm and their funding?

With calculations, estimates, and guesses from “experts” (who presumably work at the WWF). Their guesses range between 200 and 100,000 species becoming extinct each year.

This is like saying the answer to 2 + 2 is somewhere between 1 and 500.

But since the WWF’s founding in 1961, hardly any notable species have gone extinct. Not the cute Panda Bears or Harp Seals, nor Bald Eagles, California Condors, or even the Platypus.

Either the WWF has been doing a fantastic job, or, there really isn’t that much for them to do.

A ‘poster-worthy’ extinct species would help prove the WWF’s relevance, and so in 2011 with a little biological hair-splitting, they found a couple.

The Western Black Rhino and the Eastern Cougar.

Both are amazing looking creatures, sure to generate the desired press coverage, sympathy, funding, Facebook posts, and enduring relevance of the WWF.

But were they really extinct?

The definition of “species” has been debated for centuries, with two approaches used by different people at different times.

Those two definitions are:

This is the predominant view, and for example holds that animals of very different appearances such as German Shepards and Chihuahuas, are both part of one species: Dogs.

This definition has fallen out of favor, especially since it was used in the recent past to justify slavery and genocide, by arguing that the various races of people were different species.

Nevertheless, it was this latter approach to species that the WWF used when it proclaimed that the Western Black Rhino and Eastern Cougar were extinct.

The inclusion of a location in each of those “species” names provides an important clue.

Black rhinos are simply no longer found in Cameroon, and cougars no longer found in Tennessee and Kentucky.

But there are plenty of Black Rhinos in Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa, not to mention numerous zoos across America, just as there are plenty of cougars found in Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana.

You can probably go to the zoo and see a black rhino today…

Expanding the time frame to the beginning of the industrial era, the list of extinct “species” does get longer.

But what kind of species were they?

And why did they become extinct?

It doesn’t take a lot of effort to see that the vast majority of extinct species were residents of islands.

Many of these islands were, and are, undeveloped, sparsely populated, and have little modern industry. Even a continental island like Australia is still mostly uninhabited.

So what was so dangerous to species that lived on these islands?

These island species were simply not able to compete with more robust foreign species that arrived on visiting ships. And so they were replaced, not by hunting, pollution, or the building of houses, but by an accidental sort of evolution.

In the survival of the fittest, they lost.

Of extinct mammals, most were some kind of rat, bat, or marsupial, which were replaced by more efficient, but equally ugly, European rodents.

There are still plenty of rats and bats. The function that the original species played in local ecosystems are now fulfilled by new species.

Surely mankind’s industry and expansion across Europe, Asia, and America have devastated the animal kingdom, right?

Not really.

Over the past 100 years, only 17 mammal species that did not live on islands are listed as having gone extinct.

Many of these were the same sort of extinction as the WWF’s Western Black Rhino and Eastern Cougar. Not the disappearance of an entire species, but of a variation, from a particular place. They are:

Before jumping to conclusions about the “irrevocable harm to the ecosystem,” or the “scourge of mankind,” it might be wise to examine a few of these “extinctions” to see what really happened:

This sub-species of elk used to roam the Southwestern United States, becoming extinct in 1906 when European settlers began to cultivate the land.

It appears to be a case where humans and wildlife were incompatible. Except that its not.

Seven years later, Elk from Yellowstone Park were introduced to the area, where they live quite happily to this day. Unless it’s hunting season, because they are now so numerous that humans are allowed to shoot them.

In any case, the impact to the ecosystem has been approximately zero.

—————————————————————————————————-

When the Romans wanted to feature lions in the Coliseum, they took them from the Atlas Mountains in Northern Africa.

But it wasn’t until centuries later that lions ceased to be found there. Falling prey to hunters and a shortage of food in what has always been mostly desert.

Lions of course are not extinct, they are simply not found in the Atlas Mountains anymore.

It is the same situation for the Mexican Grizzly Bear. Lions and grizzly bears are still very much with us, just not in North Africa and Mexico.

Like the WWF’s Western Black Rhino, these are dislocations, not extinctions.

—————————————————————————————————-

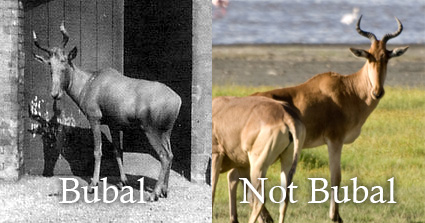

Like the Barbary Lion, the Bubal Hartebeest used to be found in the Atlas Mountains in Africa – a sparsely populated, mostly desert area with little food, and very undeveloped especially back in 1923 when the last Bubal Hartebeest was seen.

There are plenty of other types of hartebeest roaming the plains of Africa, just not bubal ones. Their disappearance certainly cannot be blamed on human “overdevelopment” in what is some of the least developed land on earth.

—————————————————————————————————-

The Wisent looked remarkably like the North American Bison. Along with the Caucasian Moose, the Cape Lion, and the Caspian Tiger, the Wisent used to roam the valleys of the Caucasus Mountains in what was the former Soviet Union.

It was and is a poor and undeveloped region of the world, and especially so under the food-shortages of the Communist era.

Caucasian Wisents were hunted to extinction, but not because of industrialization and modern society, but rather because of the lack of it.

If the Soviet Union had a workable economy that could feed its people, perhaps the Wisent would have been left alone to roam the valleys of the remote mountains.

In other areas of Europe, Poland, Belarus, Germany, and Romania, Wisents can still be found in the wild.

—————————————————————————————————-

This very small, untamable donkey became extinct due to overhunting and serving as a food supply to soldiers during the Turkish-Arab conflicts in Syria, Jordan, and Palestine during the First World War.

It wasn’t human overdevelopment that was to blame, but rather human destruction.

War. What is it good for? Absolutely nothing.

Not even little donkeys.

—————————————————————————————————-

According to the Red List of Endangered Species, the Red Bellied Gracile Opossum went extinct because its forest habitat in Jujuy Province, Argentina was destroyed.

It sounds like a classic case of rain-forest destruction, but it isn’t.

First of all, most of Jujuy Province is a desert, and has been for the past thousand years.

Secondly, the part of Jujuy that is forested is still forested. A satellite photo shows that the southeastern corner of Jujuy province remains mostly untouched.

Even now, the local people are struggling to build serviceable roads through the rugged terrain. Here is the “deforestation” of Jujuy… two guys and a backhoe.

The Red Bellied Opossum was last reported seen in 1962. But it wouldn’t be a great surprise if there were still a few running around in the hills above Jujuy.

—————————————————————————————————-

And so it goes on down the list.

The “Mexican” Grizzly Bear is extinct, but there are plenty of grizzly bears elsewhere.

There are no more mice in Bulow Florida, but there are plenty of mice in the rest of the state.

One has to look long and hard to find an “actual” species extinction without resorting to the kind of hairsplitting as practiced by the WWF with the Western Black Rhino.

And yet, one does not have to look far at all to find anti-human sentiment and legislation in our everyday lives.

But fundraising based on scary stories should not trump reality.